More Than A Court

Establishing Brandywine Court Tennis at Hagley is much more than pairing a vacant building with a unique sport. There are at least two fascinating stories that can be shared with the public in the union: the story of the du Pont family’s arrival in the United States and the history of the New Machine Shop.

In addition, Brandywine Court Tennis offers the opportunity to explore Pierre du Pont’s connections to some the most influential men of his era, including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Marquis de Lafayette, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, and Antoine Lavoisier.

With input and approval from Hagley, these stories can be told through exhibits incorporated in the design of the Brandywine Court Tennis facility.

P.S. du Pont and the Tennis Court Oath

The du Pont family’s arrival on the banks of the Brandywine starts, in some ways, with a court tennis court, known as jeu de paume in French.

In Spring 1789, King Louis XVI gathered the Estates General at Versailles. Among the members of the Estates General was 49-year-old Pierre Samuel du Pont, an advocate for constitutional monarchy and representative for the Third Estate of Nemours. The group's calls for democracy gained traction, and King Louis attempted to quash their movement by locking the doors to where they met.

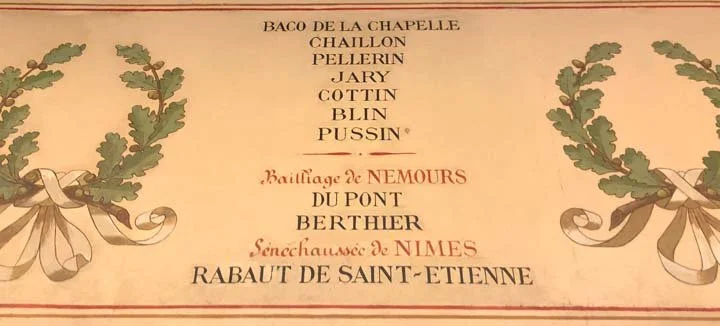

On June 20, 1789, the Estates General found the doors locked and withdrew to the nearby jeu de paume court, where the royal family, especially the King, played court tennis. There, the Third Estate vowed, in what became known as The Tennis Court Oath: “We swear never to separate and to meet wherever circumstances required until the kingdom’s Constitution is established and grounded on solid foundations.” In The du Ponts: Portrait of a Dynasty, Marc Duke writes, “In his turn, Pierre DuPont de Nemours signed the Tennis Court Oath” alongside 575 other representatives of the Third Estate. Versailles now refers to the Tennis Court Oath as the “founding act of French democracy”

Pierre’s calls for moderate constitutional reform soon gave way to Maximilien Robespierre’s radicalism. In August 1792, armed revolutionaries stormed the King’s residence at Tuileries Palace. Pierre and his son Eleuthére defended the royal family from the attack as they retreated to the Legislative Assembly. Within four months, the Robespierre-led mob abolished the monarchy and executed the King. For his role in defending the royal family, Pierre was sentenced to be guillotined as well. His life was only spared when Robespierre died in July 1794, marking the end of “The Terror.”

Pierre tried to resume life in France, but his house was ransacked as revolutionaries continued to take to the streets. In 1799, ten years after he and the Third Estate sparked the French Revolution on the jeu de paume court at Versailles, Pierre, his sons, and their families departed France, arriving in the United States in 1800.

Fifteen years later on February 28, 1815, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Pierre upon the end of Napoleon’s first reign as Emperor (but before Napoleon’s last period of rule known as The Hundred Days or the War of the Seventh Coalition):

“I have to congratulate you, which I do sincerely on having got back from Robespierre and Bonaparte, to your ante-revolutionary condition. You are now nearly where you were at the Jeu de paume on the 20th of June 1789. The king would then have yielded by convention freedom of religion, freedom of the press, trial by jury, Habeas corpus, and a representative legislature.”

The New Machine Shop

Architecturally massive and imposing, the New Machine Shop holds a distinctive position in the history of the DuPont Company and the conclusion of DuPont’s gunpowder manufacturing along the Brandywine River.

From its founding in 1802, DuPont grew quickly. By the mid-19th century, it was one of the leading suppliers of explosives for the mining and construction industries. DuPont's Brandywine powder mills became a key producer of black powder for the U.S. Army and Navy in every major American conflict from the War of 1812 through World War I.

The New Machine Shop was constructed between 1904-05 to address the growth and the increasing infrastructure needs of the powder mills. Within the Shop, workers fabricated and repaired machinery, rail cars, wagons, and other items. The section of the property where the building sits also included a carpentry shop, stone-mason shops, pipefitters and boilermakers, keg and container storage, as well as a freight rail line to move raw materials.

In 1912, as a result of the Sherman Antitrust Act, the U.S. Department of Justice ruled that DuPont’s dominance of the explosives business constituted a monopoly and ordered a divestment. DuPont's focus gradually shifted toward chemicals and materials science. The company turned part of the original powder yards into a research and development facility called the Experimental Station. There, scientists created DuPont products such as neoprene, cellophane, and nylon. The New Machine Shop provided repair and fabrication services that helped get the Experimental Station established.

DuPont closed the Brandywine powder mills in 1921, along with the New Machine Shop. All machinery and tooling were redeployed to DuPont's machine shops on the Christina River, located near where the present Market Street Bridge stands.

Hagley’s Former Historian Lucas Clawson writes, “The New Machine Shop is a rare extant example of early 20th-century industrial architecture in the Brandywine Valley. The building has not been significantly altered since 1921, making it one of the few intact sites that document Wilmington’s significant industrial history.”

Franklin, Jefferson, Napoleon, and More

The New Machine Shop and its associated histories present an opportunity to explore Pierre du Pont’s connections to some the most influential men of his era. At the time of the Tennis Court Oath and the resulting French Revolution, du Pont was corresponding with notable figures including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Marquis de Lafayette, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, and Antoine Lavoisier. Many of their letters are now housed at Hagley.

Franklin, the “Electrical Ambassador,” enjoyed great publicity during his stay in France. “It is universally believed in France,” wrote John Adams from Paris, "that his electric wand has accomplished all this revolution.”

Simon Schama writes in Citizens: “Not surprisingly [the] equation of liberty and lightning was eagerly endorsed in the Revolution, so that in Jacques-Louis David’s pictorial account of the Tennis Court Oath, for example, a bolt of electrically-charged freedom cracks over Versailles as a great gust of wind blows fresh air through the crowd-filled window spaces.”

Franklin had been at Versailles in March 1778 to negotiate French support for American Independence, and he later developed an ongoing correspondence with du Pont, more than 30 years his junior. Du Pont later wrote of Franklin, “His large forehead suggests strength of mind and his robust neck the firmness of his character. Evenness of temper is in his eyes and on his lips the smile of an unshakeable serenity."

Just three years after the French Revolution drove du Pont from his native country, President Thomas Jefferson, an ardent supporter of the Tennis Court Oath, engaged Pierre to “convey unofficially to Napoleon Bonaparte a threat against the French occupation of Louisiana,” according to The History of the E.I. Du Pont de Nemours Powder Company. Jefferson wrote to du Pont, “this little event of France possessing herself of Louisiana ... is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both shores of the Atlantic and involve in its effects their highest destinies.”

Du Pont served as an advisor to Jefferson and negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with Napoleon, though the French Emperor and du Pont privately disliked one another.

The Tennis Court Oath also relates to Éleuthère du Pont’s mentor and teacher, Antoine Lavoisier. Lavoisier, who discovered the role of oxygen in combustion, trained young du Pont on the production of gunpowder in France. In 1791, Lavoisier loaned Pierre 71,000 livres to start a newspaper covering government reforms and scientific development, but the Revolution soon turned on the father of French chemistry.

Lavoisier was accused of defrauding the state, and he was guillotined in May 1794 (just two months before the death of Robespierre), though the French government later admitted that he was falsely convicted. In June 1803, Éleuthère wrote to his father that he planned to change the name of the company’s mills from “Eleutherian Mills” to “Lavoisier Mill” because it “would never have been started but for his kindness to me.”